I've turned a version of the talks I've been doing on 'AI in libraries' for the past few years into an article for a library magazine. This is very much a pre-print, but it'll serve to capture a moment in time. Apparently it's an 11 minute read.

Artificial Intelligence has become one of the most discussed technologies of our time, but what does it actually mean for libraries and other cultural heritage institutions? In a decade working in digital scholarship at the British Library, I've witnessed firsthand the potential for AI to transform access to our collections – while also learning about its very real limitations.

Understanding AI: Beyond the Hype

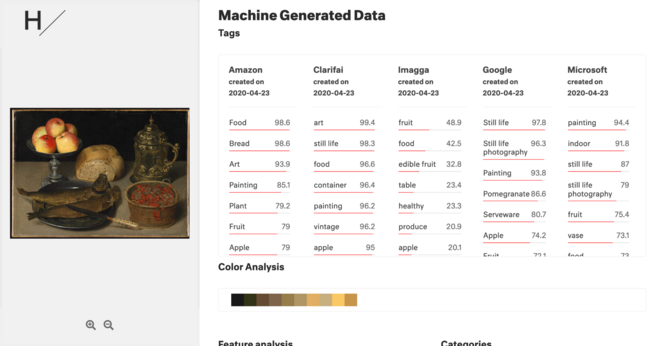

Before exploring what AI can and can’t do for libraries, it's worth defining what we mean by AI. The term encompasses several related technologies that have evolved over time. Several years ago we talked about digital research with big data, then we were excited about machine learning and data science methods for developing software that was able to complete more complex tasks. We experimented with assistive or discriminative machine learning tools that could transcribe handwritten text, predict tags for images, detect entities like people, places and dates in text, or correct your spelling. These tools were useful, but relatively narrow in scope.

Now we have generative AI tools that can produce plausible new texts, images, and videos. However, it's crucial to understand their limitations: they can't count or do mathematics reliably, they don't truly understand words or concepts, they can't grasp real-world physics, and they can't determine truth.

I often use an image I generated with an AI tool using the prompt ‘rare books and special collections’ to illustrate this point. The result looks impressive – it has all the visual elements we associate with ancient books, including leather binding and aged paper. But when you examine it closely, it's a physically impossible ‘book’. The pages can't be opened; the text can't be read. It captures the superficial appearance of a rare book without any of the characteristics of a physical book. This perfectly demonstrates both AI's impressive capabilities and its fundamental limitations.

Figure 1 An image generated by AI with the prompt ‘rare books and special collections’.

Or to put it more flippantly, we call it 'machine learning' when it works, and 'AI' when it doesn't.

Practical Applications in Library Collections

Despite these limitations, AI and machine learning offer significant benefits for libraries. One of the most powerful applications for libraries is automatic text transcription from images and audio. A whole world of possibilities opens up once you have digital text.

Librarian and developer Matt Miller demonstrated what is possible with an early version of GPT: he took digitised images of a handwritten historical diary, and used AI to automatically transcribe the text, generate summaries of each entry, extract dates and locations, and identify people and places mentioned within. This transforms previously inaccessible handwritten documents into searchable, structured data which can be used in research or to find related items. Entity detection and linking – identifying people, places, dates, and concepts within text – allows us to create rich connections across our collections.

Object detection in images is another breakthrough. AI can identify items in photographs and generate keywords, labels, and descriptions. This technology is probably already working on your smartphone – you can search your photos for concepts like ‘dog’ or ‘dinner’, or select, copy and paste text from a photo. For libraries, this means our visual collections become much more discoverable.

Perhaps most importantly for library users, AI can cluster similar images and words, enabling conceptual rather than keyword-based searching. Instead of users needing to know how library catalogues work, they can search for ‘vibes’ or concepts, making library collections far more accessible to diverse audiences.

We can also translate text and speech into other languages – if you attended my talk at Knihovny současnosti 2025, then you probably saw the live transcription and translation of my Australian-accented English into Czech subtitles. AI can also rewrite content for different audiences, perhaps explaining complex research for tourists or children.

As an example – the process of writing this article was augmented by AI/machine learning tools. I recorded my rehearsal and live delivery of my conference presentation, then copied the text transcriptions my phone generated from those recordings into an AI tool (Claude AI). I asked the tool to turn my spoken words into an article, then edited the result into the article you’re reading now. It’s all my own thoughts, but with a level of polish that it would have taken me a lot longer to produce.

Building Institutional Capacity

The British Library's experiments with machine learning and AI didn’t happen overnight. We've invested in training and digital literacy around AI and machine learning for over a decade as part of our broader digital scholarship programme. This long-term commitment has made an enormous difference in our staff's ability to undertake experiments and be effective collaborators.

When researchers or external partners approach us with digital research projects, our staff have a sense of what might be involved, ideas for improvement, and suggestions for avoiding common pitfalls. In addition to the extensive skills required for their own jobs, this knowledge comes from hands-on experience with specific tools to understand both their capabilities and limitations, and most importantly, learning about the substantial work required to prepare data for these systems.

As we used to say in data visualisation and data science, 80% of the work is cleaning and preparing data, while only 20% is the exciting analytical or work. This remains true for AI applications in libraries.

Real-World Experiments and Collaborations

Our institutional capacity has enabled numerous experiments. For example, computational linguists analysed web archives to track how language evolves over time. For example, the term ‘blackberry’ shifted from being associated with fruit to smartphones and keyboards during BlackBerry's market dominance, then reverted as the company declined. Similarly, ‘cloud’ transformed from a meteorological term to a computing concept.

Elsewhere, Library staff developed machine learning models to detect mislabelled images in our digitised manuscript collections and created systems to identify when digitised images are upside down so they can be automatically corrected. One particularly successful project used machine learning to identify languages on title pages of digitised books. Combined with crowdsourcing verification through the Zooniverse platform, this work added 141 previously unidentified languages to our catalogue.

Our work with automatic text recognition (ATR) spans printed materials using optical character recognition (OCR), handwritten materials using handwritten text recognition (HTR), and hopefully in the future, speech-to-text for audio collections. Colleague Adi Keinan-Schoonbaert has focused particularly on extending these capabilities to non-English and non-Roman scripts – Arabic, Japanese, and other languages that aren't as well-resourced as English in current AI systems. Our work has shown how important it is to understand work you seek to automate – we talk to staff across the Library to understand their processes.

Case Study: Living with Machines

The Living with Machines project represents our most ambitious exploration to date of AI's potential for historical research. As principal investigator Ruth Ahnert described it, this was simultaneously ‘a data-driven history project and a historically informed data science project’.

We chose the name ‘living with machines’ deliberately. In 2017-2018, we realised we were on the cusp of a machine learning-led transformation that would eventually fundamentally change society. The project's meta-nature involved using 19th-century texts, newspapers and maps to understand how mechanisation transformed that era, thereby helping us understand our own relationship with emerging technologies.

British Library staff initiated the project in part to understand how machine learning was going to transform what library professionals and researchers could do with collections. We wanted to understand what AI could do well, and where it was likely to fail. The project also allowed us to explore some of the complex copyright issues around computational access (including the vital role of the text and data mining exception) and the biases potentially introduced through the selection of items for digitisation.

This massive undertaking involved over 40 people across its lifetime, typically 20-25 simultaneously. The scale reflected both the enormous collections we were analysing – millions of digitised newspaper pages and books – and our ambition to understand what happens when you bring together humanities scholars, library professionals, software engineers and data scientists to solve complex problems.

The project produced remarkable bespoke tools that responded to the challenges of working with digitised sources at scale. Place names can be slippery – it’s important to distinguish between different locations with the same name worldwide and understand when ‘Brussels’ refers to EU governance versus the physical city, so the toponym resolution system, T-Res, could identify and disambiguate place names in text. Other team members developed methods for tracking individuals across census decades, allowing them to understand how occupations changed over time.

Linguistic analysis revealed how machines were given human-like agency in historical texts. We combined crowdsourcing and vector databases to examine how mechanisation changed the meanings of words like ‘trolley’ and ‘cart’ as railways and automobiles transformed transportation.

Additional work included developing tools for searching through poor-quality optical character recognition, understanding potential biases in our digitised newspaper corpus, and pioneering computer vision approaches for reading historical maps and extracting semantic information from cartographic symbols. Impressively, the tool designed to search across Ordnance Survey maps has been adopted by scientists outside the project.

The Current Landscape: From Custom to Commodity

The AI landscape has evolved dramatically since we began Living with Machines. Wardley Mapping proposes that technologies pass through successive ‘evolution’ stages. The Living with Machines project operated during the ‘custom-built’ stage, when AI and data science tools were experimental and unique, requiring specialist expertise to build. This also allowed the project to co-create bespoke tools with humanities scholars.

Today it is much more likely that libraries can find existing products that meet their needs for common tasks like text and speech recognition, detecting objects in images, keyword search expansion, and even suggesting subject headings. Tools like ChatGPT and other large language models have made tasks possible now that were impossible in the early years of Living with Machines. Library professionals can experiment with AI tools on their desktop to prototype bespoke workflows and tasks.

Challenges and Limitations

However, we don't yet have the AI that libraries truly need and deserve. Current machine learning models embed prejudices – particularly racism, sexism, and structural inequalities expressed in historical training data. They don't represent all cultures or historical periods equally, and they often reflect commercial rather than cultural heritage values.

Ethical questions surround how training data was obtained, with numerous ongoing legal cases addressing these concerns. Environmental costs can be substantial, and companies aren't always transparent about water usage and carbon footprints.

Most critically for libraries – institutions that prize accuracy and precision – we know AI-generated content contains errors, but we can't predict where they'll occur. Even with error rates as low as 5-10%, we must carefully consider where mistakes are acceptable. Less precise keywords might be fine for discoverability, but errors in authoritative catalogue records are more problematic.

Since we often need to manually check everything or conduct sample validation anyway, it's sometimes unclear how much time these tools really save.

Looking Forward: Community and Continuous Learning

Despite these challenges, AI technologies continue advancing rapidly. What seems impossible today may be routine in a year's time.

Of course, this can make it hard to keep up with changes in the field. I encourage everyone to engage with communities like AI4LAM (Libraries, Archives, and Museums), which hosts regular online calls about different topics and maintains extensive archives of previous sessions on YouTube. They also provide Slack channels and a mailing list for ongoing conversation. These resources offer invaluable insights into how different organisations tackle specific challenges and enhance their collections.

British Library staff, particularly my colleague Nora McGregor, helped develop Digital Scholarship & Data Science Topic Guides for Library Professionals (DS Topic Guides). These topic guides were written specifically for busy librarians to provide quick topic overviews and point toward additional resources. We welcome contributions from the broader community.

Conclusion

AI and machine learning offer genuine opportunities to transform how we work with library collections, making them more accessible, discoverable, and useful for researchers and the public. However, success requires understanding both the potential and limitations of these technologies.

The key lies in building institutional capacity through training and experimentation, working collaboratively with technical experts, and maintaining critical awareness of biases and limitations. Most importantly, we must remember that AI works best when it augments human expertise rather than replacing it.

As we continue living with these machines, the goal isn't to automate everything, but to amplify our capabilities while preserving the values and standards that make libraries essential cultural institutions. The future of AI in libraries will be written by practitioners who understand both the technology and the unique mission of libraries in preserving and sharing human knowledge.

I called my talk '57 varieties of digital history' as a play on the number of activities and outputs called 'digital history'. While digital history and digital humanities are often linked and have many methods in common, digital history also draws on the use of computers for quantitative work, and digitisation projects undertaken in museums, libraries, archives and academia. Digital tools have enhanced many of the tasks in the research process (which itself has many stages – I find the

I called my talk '57 varieties of digital history' as a play on the number of activities and outputs called 'digital history'. While digital history and digital humanities are often linked and have many methods in common, digital history also draws on the use of computers for quantitative work, and digitisation projects undertaken in museums, libraries, archives and academia. Digital tools have enhanced many of the tasks in the research process (which itself has many stages – I find the